Have you ever listened to a chronic complainer and found yourself getting upset? You may have felt frustrated when you offered advice, distraction, humor, or affirmation and the complainer complained even more. One can feel sucked into a vortex of negativity when listening to someone who perpetually complains. Nothing seems to snap the complainer out of his negativity. Our reaction to a complainer is an indication of what is really going on: an emotional message, in the form of a reaction loop, about how we are communicating. The way to deal with a complainer is to see your frustration as a signal to look at the inner process of communication and shift into “Deep Listening” mode.

The first step in dealing with complainers is to understand that most people who complain aren’t asking for advice, solutions, or cheerful affirmations (Burns, 2010). Instead, they want someone to listen and accept how they feel; they need to know they are being heard, understood, and validated. It is almost as if a question is being asked: “Is it okay for me to feel something, does anyone accept that I am upset?” Rather than a literal invitation to solve a specific issue, complaints and your reactions are about meta-communication, emotionally charged messages about connection, telling you that communication with another may be hung up on interpretation, assumption, or bias. It is painful to hear things we don’t agree with when we are on the receiving end of a long line of complaints. We take issue with the complaint; we take it personally. When listening to someone complain, most people are gathering evidence to state their opinion, rebuttal, or advice; biding their time until they can speak. This is especially true when listening to a complainer. A complaint can amplify our own inner insecurities. For example, we can feel upset when advice or humor are brushed off; the speaker then may feel upset at not being heard, upping the ante, and a negative reaction loop is born. We cannot truly listen when we are full of our own indignation, need to help, righteousness, or desire to see things differently. The first law of deep listening is to put our ego aside and listen to another’s truth.

Deep listening is listening without ego response. We hear another with our whole awareness, being as attentive as if we were in a soaring Cathedral or place of vast natural splendour, listening into the spirit of the moment, held in silent rapture by its inherent wholeness, beauty, and integrity. We do not expect waves on the beach to adjust to our needs and not wet our shoes (as king Canute); we simply attend and listen. The same is true in deep listening with another. When we put aside our need to hear things in a certain way, we can attend to the other as a wholly different person, beautiful in his or her own right. We don’t have to agree with what the other says; we just need to see it as their truth. There are many layers to communicating, including messages about how we are communicating; we can only hear theses messages when we avoid getting caught in our reactions. Deep listening requires a certain amount of psychological maturity, an ability to put aside righteous indignation that our well-being is on the line. Instead, we listen past our own needs.

Just as we may react to a complainer, others can react when we express our reality; they may even see us as the complainer. Two people struggling to be heard does not a conversation make. The second law of deep listening is that when you find yourself in a power struggle to be heard, switch into listening, putting aside your emotional reaction about not being heard. (Not that you will never be heard, but timing is key; first an emotional connection must be made.) With a sense of curiosity (versus judgment) about the thoughts, feelings, and sufferings of the other, tune into their reality. A few tools can help here, such as using thought and feeling empathy, and genuine inquiry—“It sounds like you do not agree. Is that right?” Using “I feel” statements requires an emotional shift on your part from other-blame to owning your own perceptions and emotions. For example, “I feel bothered that I may have stated my opinion too strongly and did not hear yours. Can you tell me more about what you feel?” Deep listening also requires detachment from the outcome–from thinking that, “Now that I’m listening to you must change,” or “Now you must hear me.” Instead, listen with all your senses and without trying to get the other to say what you want to hear.

I had a colleague, a helping professional, who would ask people at the office how they felt and then immediately deny those feelings, proffering personal preferences instead. I found myself frustrated after talking to her, wanting to say, “I hope you don’t do this with your clients; it’s really annoying.” I felt her positivism was wearing big bully boots. Of course, I didn’t say that; it would have only have made her defensive. After a few interactions, I realized what was really going on—I was reacting to not being heard and she needed validation. The next time she asked me how I was doing I responded, “I think I am not doing a good job of hearing you all the time; how are you doing?” When tempted to get frustrated, I asked, “You seem to have something important to say about this. Can you tell me more?” She enthusiastically told me about her philosophy. Only later did she talk, guardedly, about her personal life, which was not so cheerful. It was a good lesson in emotional Aikido—instead of fighting for my approach I entered into her reality and the interaction shifted.

Carl Rogers said that not being heard is a crazy-making form of communicating. In contrast, there is a deep sense of relief when one feels truly heard. Being “listened to by someone who understands makes it possible for persons to listen more accurately to themselves” (Rogers, 1980, p. 159). When we truly listen, often a complainer shifts (Burns, 2010). In the end, complainers just want to know that someone cares how they feel. Once my colleague felt validated, the tone of our interaction changed. Deep listening is not a magic button, not everyone will transform from complainer to enlightened listener when heard, but it does deal with our own frustration. It filters our ego so that we can be fully present with another; a good skill for all relationships.

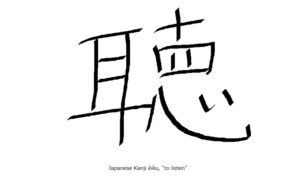

The Japanese Kanji Character for “to listen” 聴 includes the symbols for ear 耳, eye 目, and heart 心. It reads, “In listening carefully I give you my ears, my eyes, and my heart—my full awareness”; a superb image of deep listening.

(David Burns, Feeling Good Together: The secret to Making Troubled Relationships Work. (2010). Carl Rogers, A Way of Being, 1980.)